NOIR CITY: CHICAGO 2019

Music Box Theatre, Chicago, IL

Friday, September 6th, 2019 to Thursday, September 12th, 2019

KISS ME DEADLY (1955)

United Artists, 106m

*Presented as it was released in 1955; in 35mm courtesy of Park

Circus

"Remember me when I

am gone away,

Gone far away into the

silent land;

When you can no more

hold me by the hand,

Nor I half

turn to go yet turning stay.

Remember me when no more

day by day

You tell me

of our future that you planned:

Only remember me; you

understand

It will be

late to counsel then or pray.

Yet if you should forget

me for a while

And

afterwards remember, do not grieve:

For if the darkness and

corruption leave

A vestige of

the thoughts that once I had,

Better by far you should

forget and smile

Than that

you should remember and be sad."

—"Remember," Christina Georgina Rossetti (December 5,

1830 — December 29, 1894)

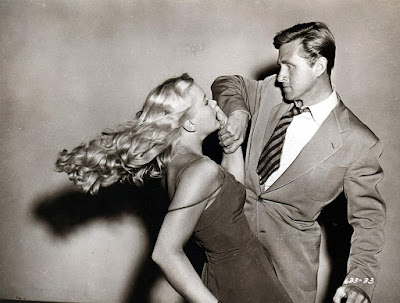

KISS ME DEADLY may be the finest of film noirs released in

the 1950s, but author Mickey Spillane was not impressed with what screenwriter

A.I. Bezzerides did to his novel. According to event host Eddie Muller, founder

and president of the Film Noir Foundation, Spillane said all that remained of

his sixth novel to feature private investigator Mike Hammer was the title. The

leftist writer Bezzerides obviously did not think much of Spillane's signature

character, and went the extra mile to make sure he could not be construed as

the hero of the filmed adaptation. Whether one likes the onscreen Hammer figure

or not, there is much to admire about the film world he inhabits. Despite

adherence to the usual dictates of film noir, KISS ME

DEADLY does not look or sound quite like any other noir film.

In comparison with other examples of '50s noir, it seems oddly

contemporary; its main difference from the modern crime story is the absence of

ubiquitous f-bombs. The nihilistic production also benefits from unrelenting

toughness, Ralph Meeker's exceptional performance as a marginally likable heel

and some quirky female characters that seem plucked from the David Lynch

universe.

Director Robert Aldrich (WHAT EVER HAPPENED TO BABY JANE? [1962])

makes the most of an intense introductory sequence that begins with Christina

Bailey (Cloris Leachman) running barefoot down a dark highway. When Mike Hammer

(Ralph Meeker) narrowly avoids plowing into her, he shows concern only for the

preservation of his smooth ride. "You almost wrecked my car," he

grumbles in disgust. The tone is set. Next the opening credits scroll backwards over

the orgasmic panting of Christina, now attached to Mike in his convertible. She

is a fugitive from a psychiatric ward, and soon enough those seeking her make

their presence known. In an unforgettably suggestive segment, Christina is

tortured with pliers(!) by men who remain anonymous to the camera, while a

groggy Mike is helpless to intercede. The apparent leader of the villains

calmly speaks with disturbing eloquence after Christina becomes non-responsive.

The unlikely noir couple is left for dead, but Mike survives

and finds himself absorbed in a mystery he may be ill-equipped to comprehend.

Ironically for a good chunk of the film he is perplexed by a clue that reads

"REMEMBER ME." That request is a tall order for a self-absorbed man

like Mike, who parasitically feeds on divorce cases for his source of income.

The death of Christina draws the attention of the Interstate Crime

Commission, and Mike is curious as to why. The cops show complete disdain for

Mike, whose detective practice involves capturing evidence of married people

breaking their vows. Worse than that, he and his assistant Velda Wickman

(Maxine Cooper) get personally involved with the couples they target in the

interest of gathering damning information. Mike already had proven in the

opening sequence his instinct is to not cooperate with law

enforcement officials, so it comes as no surprise when he refuses to play ball

and leaves the interrogation room. One man contemptuously comments, "Open

a window." These men seem no better than Mike. Lieutenant Pat Murphy

(Wesley Addy) in particular is one smug little bastard, absolutely impossible

to like. Pat personally informs Mike that his PI license and handgun permit

have been revoked. Film noir sometimes highlights the

determination of effective public servants in examples such as T-MEN (1947), TRAPPED (1949), APPOINTMENT

WITH DANGER (1950) and PANIC IN THE STREETS (1950),

but KISS ME DEADLY finds little faith in public officials. Who

are the true villains here?

As Mike stubbornly persists in sticking his nose in where he knows

it is most unwelcome, it becomes evident he is an outsider in every way

imaginable. He associates best with other outsiders and worst with those who

feign respectability. His probable best friend is Nick (Nick Dennis), a

fast-talking, affable Greek auto mechanic. Mike is also helpful to an Italian

American burdened with what appears to be a very heavy storage chest. When Mike

gets loaded in a nightclub, he is the only white face among the black

clientele; he has more in common with people of color than other white people.

A man easily angered, Mike gets impatient with those who do not cooperate. He

delights in pushing people around, and he can take a punch as well as anybody.

Sometimes when he gets tough it is easy enough to side with him, as when he is

first confronted by Charlie Max (Jack Elam) and Sugar Smallhouse (Jack Lambert).

Other times Mike makes it difficult to gain the viewer's allegiance. The deeper

he gets into his investigation, the more crude slaps he dishes out, as when he

roughs up a meek front desk clerk. The PI is especially mean-spirited when he

breaks an opera fanatic's classic record, even more so when he crushes the

fingers of Doc Kennedy (Percy Helton) in a desk drawer. In those two instances

of highly questionable procedure, the camera captures Mike's admiration for the

type of work he enjoys all too well. The film noir often uses

narration to smooth over a lead protagonist's rough edges to encourage the

viewer to identify with that individual. The absence of narration in KISS

ME DEADLY marks a genre in transition, as well as a main character we

are not meant to admire. Even if the viewer should not condone Mike's tactics,

it is difficult not to empathize a little after the brutal killing of his

friend causes the gumshoe to go berserk.

Though critics and fans often brand Mike a stupid individual, I

think he is better described as a boorish, egocentric character who is out of

his element, a type of man whose time has passed. He is intelligent enough and

experienced enough to know a big case when he stumbles onto one, and he proves

his street smarts on numerous occasions, especially when he correctly deduces

what became of a small artifact associated with Christina. He also predicts the

location of two incendiary devices placed within the

automobile he was gifted by those who would celebrate his violent demise. In a

wonderfully intense conversation, Carl Evello (Paul Stewart) admits his

organization has underestimated Mike repeatedly. Mike's instincts prove less

reliable when he encounters a package equipped with far superior firepower

compared with what was found in his newest car. The air of fatalism that

chokes film noir characters comes neatly packaged, but

dangerous to the touch. Mike's first exposure to "the great whatsit"

as Velda describes it creates a painful brand on his wrist (we know it is

serious when the proven tough guy Mike winces!). That event marks Mike for death.

"If you had not

stopped to pick up Christina, not any of these things would have

happened..."

KISS ME DEADLY features about the oddest assortment of revisionist femme

fatales ever to grace a noir film. Christina latches onto Mike

in the opening sequence, despite his immediate disdain for her highway obstacle

act. Would he have invited her into his car had he not imagined her naked under

that trench coat? Probably not. Interestingly, only after Christina pokes Mike

about his self-centered masculinity does he begin to loosen up a little in

front of her. But in most prime examples of noteworthy noir themes,

Mike would have been the wiser to allow Christina to fend for herself (she may

have been better off as well). His chance involvement with Christina leads to a

deadly connection with the mysteriously mousy Lily/Gabrielle (Gaby Rodgers)

that has consequences far greater than anything Mike may have considered. And

though her screen time is brief, Friday (Marian Carr) strikes a chord as

perhaps the most weirdly amorous dame to appear in a noir film.

In another example of his better judgment, Mike shows some restraint when

confronted with her aggressive advances.

|

| Point that thing somewhere else |

The "good" girl has her share of baggage, too. Velda is

always hot for Mike, and she certainly is an attractive brunette, but the

sadomasochistic Mike would prefer to pimp her out in service of his trashy

detective enterprise. She puts it well in the hospital sequence in the first

act when she tells him, "You never need me when I'm around." The

hotter she gets, the cooler he treats her, and his head usually turns when

another skirt walks by. That is not to suggest he harbors no attraction to Velda,

but her ability to seduce any other man means more to him than whatever

feelings he holds for her. During the opening scenes, Christina correctly

identifies Mike as a man who cares only about himself, a man who cannot give,

only take. Ultimately that quality condemns him. In light of the film's

devastating concluding sequence, Mike (and many others) would have been

grateful had he granted Velda the alone time she always desired and steered

clear of crazed blondes. But upon repeat viewings of the film, Velda's neediness

is a little pathetic. She wants Mike more than any man would wish to be wanted.

The fine screenplay is complemented by cinematographer Ernest

Laszlo (IMPACT [1949], D.O.A. [1949]), who relies

heavily on the use of oblique camera angles, particularly in the early going. A

nice touch I noticed for the first time at this event's screening is the

emphasis given to the hydraulic floor jack used to quickly service Mike's

vehicle after he picks up Christina—one of those devices has a role in a

gruesome murder later in the story. Laszlo's coverage of complex stairways,

both interior and exterior, stands for the complicated and hazardous noir labyrinth

through which Mike travels. Many of the interior staircases are ornamentally fabricated;

most exterior staircases are unusually high and would make for an exceptionally

painful way to take a tumble (as a thug tailing Mike learns). That stairway

fall always makes me gasp—somebody did that stunt! According to Eddie Muller,

that scene utilized an actual staircase with no special padding.

The conclusion of the film intended by director Robert Aldrich was

not reinstated until 1997. The truncated ending in which nobody escapes the

beach house may have been less open to interpretation, but neither version

suggests a different end result for the lead protagonist, who forfeits his

future when he opens the modern equivalent of Pandora's box. In any case, I do

not think Mike should shoulder the blame for the catastrophic event that ends

the film. All the blame should go to Dr. G. E. Soberin (Albert Dekker),

who fails to take his own advice. Soberin has a lot to say about the huge

mistake Mike made when he got tangled up with Christina, but in the film's

final sequence Soberin makes a far greater error when he treats Gabrielle like

a child; the intellectual is somehow completely oblivious to her potential

danger. As the doctor's name implies, KISS ME DEADLY's ultimate

takeaway is sobering indeed.